GS Paper III

News Excerpt:

The Food inflation pressures in an El Niño and election year have reversed the relative self-sufficiency that the country has achieved in pulses which has led to rise in the import of pulses.

Retail food inflation:

- In April 2024, the consumer price index for cereals was 8.63% higher than that in April 2023.

- The government’s food security scheme, which provides rice and wheat to 813.5 million people, may have mitigated the impact of rising cereal prices.

- As a result, the majority of poor and lower middle class Indians may not have been significantly hurt by the inflation in cereal prices.

- The same cannot be said about pulses, which posted an annual retail inflation of 16.84% in April 2024 — nearly twice that for cereals.

- According to the Department of Consumer Affairs, the average all-India modal (most-quoted) price of chana (chickpea) — the cheapest available dal — was Rs 85 per kg on May 23, as against Rs 70 a year ago.

- The corresponding price rise has been even more for arhar/tur or pigeon pea (from Rs 120 to Rs 160 per kg), but less (from Rs 110 to Rs 120 per kg) for both urad (black gram) and moong (green gram). The modal retail price of masoor or red lentil has actually eased from Rs 95 to Rs 90 per kg.

Causes of the drop in Pulses production:

- The main reason is the El Niño-induced patchy monsoon and winter rain, causing a decline in domestic pulses production.

- The two pulses to register the highest inflation have both seen sharp output falls:

- chana (from 13.54 mt in 2021-22 to 12.27 mt in 2022-23 and 12.16 mt in 2023-34) and arhar/tur (from 4.22 mt to 3.31 mt and 3.34 mt).

- Trade sources peg this year’s chana production to be less than 10 mt and arhar/tur production to be below 3 mt.

- Experts say the decline in domestic output is also because of erratic climate conditions in key producing regions.

Government actions amid declining pulse production:

- Renewed food inflation pressures have forced the central government to phase out tariffs and quantitative restrictions (QR) on imports of most pulses.

- In May, 2021, the annual QRs on arhar/tur, urad & moong imports, along with a 10% basic customs duty, were lifted.

- In July, 2021, the duty on imports of masoor was slashed from 10% to nil.

- Yellow/white pea imports, till quite recently, were subject to a yearly QR of 0.1 mt, in addition to a 50% duty and a minimum price of Rs 200/kg, below which no consignment was cleared.

- All these curbs were removed in December, 2023. On May 3 this year, the 60% import duty on desi (small-sized) chana was done away with.

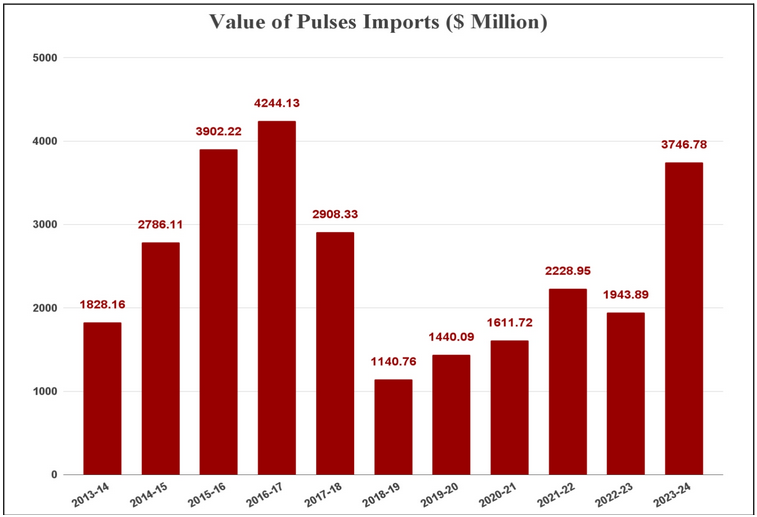

Increase in import of pulses:

- India’s pulses imports were valued at $3.75 billion in 2023-24 (April-March), the highest since the record $3.90 billion and $4.24 billion of 2015-16 and 2016-17.

- In quantity terms, import of major pulses totaled 4.54 mt in 2023-24, up from 2.37 mt and 2.52 mt in the preceding two fiscals.

- Although it was lower than the all-time-highs of 5.58 mt, 6.36 mt and 5.41 mt in 2015-16, 2016-17 and 2017-18 respectively.

- Imports of masoor, mainly from Australia and Canada, touched a record 1.7 mt in 2023-24.

- Yellow/white pea imports — from Canada, Russia and Turkey — surged from virtually nothing to 1.2 mt.

- Chana imports (mostly from Tanzania, Sudan and Australia) rose as well.

- On the other hand, imports of arhar/tur (from Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi and Myanmar) and urad (predominantly from Myanmar) have been flat.

Past Government initiatives to increase pulse production:

- The resurgence in imports marks a reversal of the relative self-sufficiency achieved by the country, with domestic pulses production increasing from 16.32 mt to 27.30 mt between 2015-16 and 2021-22.

- The increase in production was enabled by government policy measures incentivising farmers to grow pulses.

- These included MSP-based procurement and levying of duties leading to a near stoppage of imports, particularly of yellow/white peas (matar) and chana, by 2022-23.

- Domestic production got a further boost with the breeding of short-duration chana and moong varieties, making it possible to cultivate these with little or no irrigation, using the residual soil moisture left by the previous crops.

- The 50-75 day varieties of moong now allow planting of as many as four crops a year: kharif (post-monsoon), rabi (winter), spring and summer.

India is a large consumer and grower of pulses and it meets a portion of its consumption needs through imports. India primarily consumes chana, masur, urad, kabuli chana, and tur.

Way Forward:

- Dal inflation in the coming months would largely depend on the southwest monsoon.

- Global climate models are pointing to El Niño transitioning to a “neutral” phase next month.

- There could even be La Niña — associated with good rainfall activity in the subcontinent — by the second half of the four-month season (June-September).

- But the precarious domestic supply position (government agencies have procured barely any chana from this year’s crop, compared to 2.13 mt in 2023 and 2.11 mt in 2022) and monsoon uncertainties make higher imports inevitable.

- The government has already permitted duty-free imports of arhar/tur, urad, masoor and desi chana till March 31, 2025.

- It may have to extend the same for yellow/white peas imports too — beyond October 31, 2024 now.

- Yellow/white peas, being imported at Rs 40-41/kg, are a cheaper substitute for chana, just as masoor dal is replacing arhar/tur for making sambar in many restaurants and canteens.

- It is imports of these pulses — grown in Canada, Australia and Russia — that are likely to go up more than arhar/tur and urad shipped from East Africa and Myanmar.