News excerpt:

A new study published in the journal Science raises concerns about nature-based carbon removal projects, particularly those focused on forestation.

More about the study:

- Researchers have challenged the effectiveness of large-scale tree planting as a strategy to combat climate change.

- The study reveals shortcomings in current climate models that predict how long carbon stays stored in trees.

- Strategies developed by governments and corporations to address climate change rely on plants and forests to draw down planet-warming carbon dioxide and lock it away in the ecosystem.

- According to the research, these models may be overestimating the duration of carbon storage in plants and underestimating the effects of climate change on forests.

Findings of the research:

- The finding indicates that while plants absorb more carbon than previously thought, they also release it back into the atmosphere sooner than predicted.

- Researchers emphasized the limited potential of nature-based carbon removal projects and called for a swift reduction in fossil fuel emissions to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

- Studies show that plants and soils absorb 30% of carbon dioxide emissions from human activities annually, helping to mitigate climate change and its consequences.

- However, the new study highlights gaps in our understanding of this process, particularly concerning the stability of carbon storage.

Methodology and estimates:

- Various models have estimated that global net primary productivity (the rate at which new plant tissues and products are created) ranges between 43 and 76 petagrams (billion tonnes) of carbon (PgC) per year.

- These models did not show a significant trend throughout the twentieth century.

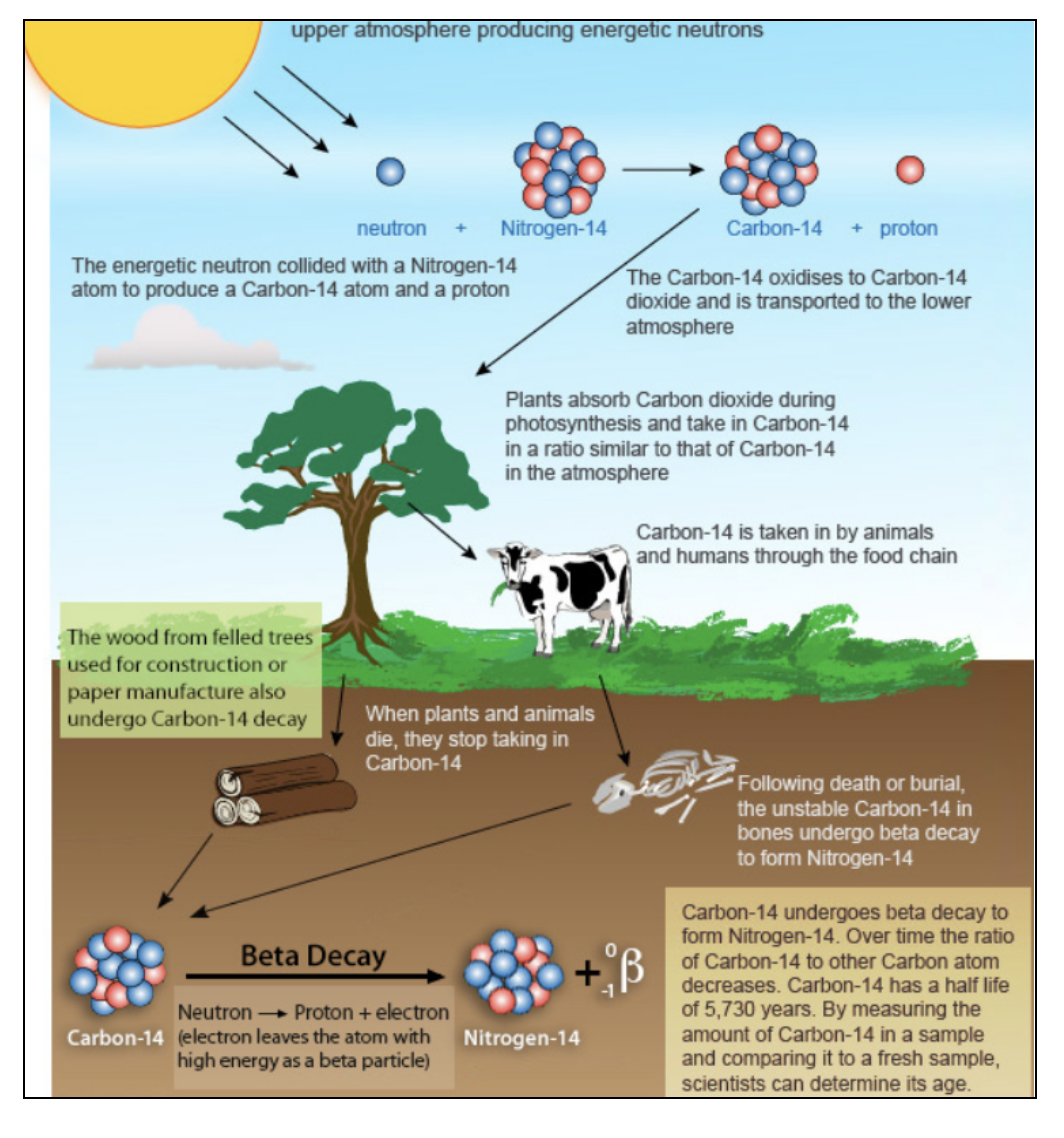

- To gain more concrete insights into carbon cycling, researchers turned to radiocarbon (Carbon-14 or C-14), a radioactive isotope of carbon.

- While radiocarbon is naturally produced, nuclear bomb testing in the 1950s and 1960s significantly increased its atmospheric levels.

- This extra C-14 was absorbed by plants worldwide, allowing researchers to track its accumulation in the terrestrial biosphere and assess rates of carbon uptake and turnover.

- They compared this to the accumulation of C-14 in plants between 1963 and 1967 when there were no major nuclear detonations.

- The researchers fed this data into models to simulate global-scale plant carbon dioxide usage and the interactions between the atmosphere and biosphere.

- Their analysis revealed that current net primary productivity is likely at least 80 PgC per year, compared with the 43 to 76 PgC per year predicted by existing models.

- The C-14 accumulation in vegetation over 1963-67 was 69 ± 24 × 10^26.

Significance and future scope of research:

- Regarding the storage of carbon from human activities in terrestrial vegetation, the study found it to be more short-lived and vulnerable than previously predicted.

- The observations show that the growth of plants at the time was faster than current climate models estimate. This implies that carbon cycles more rapidly between the atmosphere and biosphere than we have thought.

- It necessitates a better understanding and accounting for this rapid cycling in climate models.

- The paper calls for a longer analysis of subsequent decades after 1967 to gain critical insights into whole-ecosystem cycling, including litter and soil.