GS Paper III

News Excerpt:

The 2024 Environmental Performance Index (EPI), is an analysis by researchers at Yale University, USA. It provides a data-driven summary of the state of sustainability worldwide.

More details about the Index:

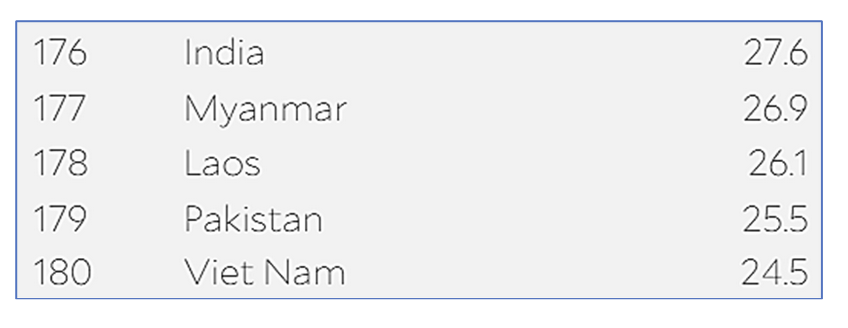

- Using 58 performance indicators across 11 issue categories, the EPI ranks 180 countries on climate change performance, environmental health, and ecosystem vitality.

- The data evaluates efforts by the nations to reach the established environmental policy targets such as the U.N. sustainability goals, the 2015 Paris Climate Change Agreement, as well as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

- The EPI offers a scorecard that highlights leaders and laggards in environmental performance and provides practical guidance for countries that aspire to move toward a sustainable future.

- EPI indicators provide a way to spot problems, set targets, track trends, understand outcomes, and identify best policy practices.

- In each iteration, the EPI expands the scope of its sustainability scorecard to reflect advances in our scientific understanding of environmental issues.

- The 2024 EPI distills data on dozens of sustainability issues into a single score.

- To make the metrics easy to interpret, it transforms raw environmental data into indicators that score countries on a 0–100 scale, from worst to best performance.

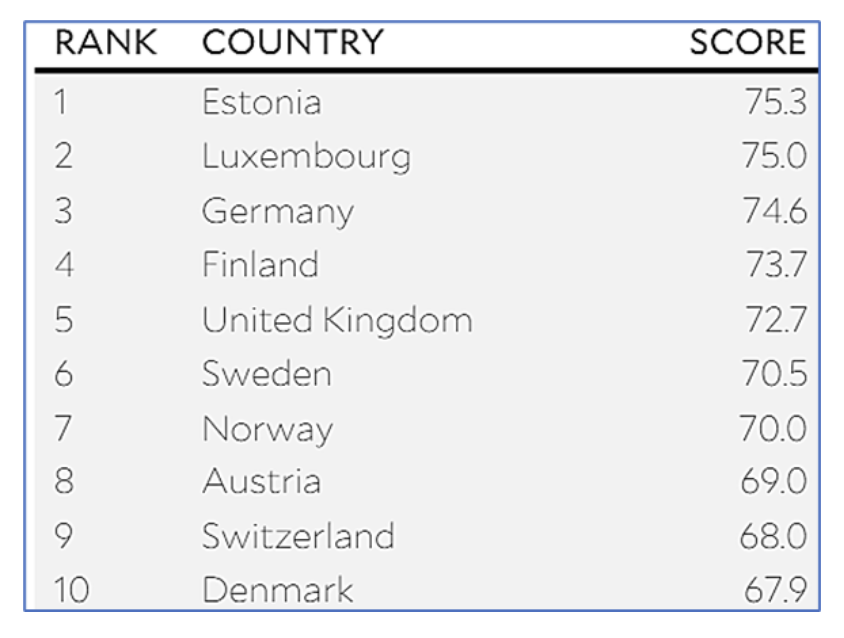

- Rank and Scores

- Estonia was placed in the 1st place in the index 2024.

-

- India, stands at 176th rank out of 180 countries, with only 4 countries below.

Executive Summary of EPI Index:

- Mounting evidence highlights the degradation of the planet’s life-supporting systems on which humanity depends.

- A world economy that continues to rely heavily on fossil fuels translates into ongoing air and water pollution, acidification of the oceans, and rising concentrations of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere.

- These changes threaten the survival of species already suffering from widespread habitat loss, pushing them closer to extinction.

- Recent analyses show that humanity has already transgressed six out of nine critical planetary boundaries that define Earth's safe operating space and is close to crossing a seventh.

- In the face of these compounding crises, an empirical, data-driven approach to environmental policymaking is more important than ever. Carefully constructed metrics allow policymakers and other stakeholders to track trends, identify successful policy interventions, share best practices, and maximize the return on environmental investments.

- This broad set of metrics is a powerful tool to track progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals, the climate mitigation targets in the 2015 Paris Climate Change Agreement, and the biodiversity protection goals in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

- Overall EPI scores help identify which countries have been most successful at addressing a wide variety of global environmental challenges, spotlighting sustainability leaders, and calling out laggards.

Key findings:

- The World is Failing to Address the Climate Crisis:

- Last year, the first global assessment of progress toward the goals of the Paris Agreement revealed a grim picture: the world is far off track. Despite the record deployment of renewable energy, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions keep rising.

- As the world enters uncharted climatic territory, there is a heightened risk of crossing irreversible tipping points in the planet’s climate system.

- In support of more effective climate action, the 2024 EPI. introduces refined metrics to track countries’ progress at curbing their GHG emissions.

- The new metrics score countries on their emissions reduction (or growth) rates while also considering their proximity to the net-zero target.

- In addition, new pilot indicators score countries on their climate mitigation efforts in relation to their allocated shares of the remaining global carbon budget — the amount of carbon that society globally can still emit before crossing dangerous warming limits — and thus better reflect the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities.

- While GHG emissions are falling in more countries than ever before, the 2024 EPI analysis of emission trends over the last decade shows that only five countries — Estonia, Finland, Greece, Timor-Leste, and the United Kingdom — cut their GHG emissions at the rate needed to reach zero by 2050. And it is unclear whether any of these nations can maintain the pace of reduction that they achieved in recent years.

- Emissions in the world’s largest economies are either falling too slowly, such as in the United States, or still rising, such as in China, India, and Russia.

- The pace of decarbonization in Denmark, for example, has slowed in recent years, highlighting that early gains from implementing low-hanging-fruit policies, such as switching electricity generation from coal to natural gas and expanding renewable power generation, are by themselves insufficient.

- Cutting emissions at the pace needed will require significant and ongoing investments in renewable energy, transforming food systems, electrifying buildings and transportation, and redesigning cities.

- New and Refined Biodiversity Metrics:

- After climate change, biodiversity loss has emerged as the most serious and irreversible environmental crisis.

- Scientists warn that we may have unleashed the sixth mass extinction in the planet’s history.

- Given that biodiversity is fundamental to ecosystem vitality and the life-supporting services ecosystems provide, this crisis endangers the stability and continuity of human prosperity.

- Responding to the urgency of halting biodiversity loss, the 2024 EPI introduces new metrics to assess how well countries protect their most important habitats.

- The 2024 EPI also introduces pilot indicators to measure the effectiveness and stringency of protected areas.

- These new metrics track key issues related to the expansion of protected areas to meet the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s goal of safeguarding 30 percent of lands and seas by 2030.

- These pilot metrics reveal that, while many countries have reached their area protection goals, many protected areas have failed to halt the loss of natural ecosystems.

- The 2024 EPI’s analyses underscore the necessity of providing protected areas with adequate funding and of developing stricter regulations in partnership with local communities.

- Tradeoffs in Environmental Performance:

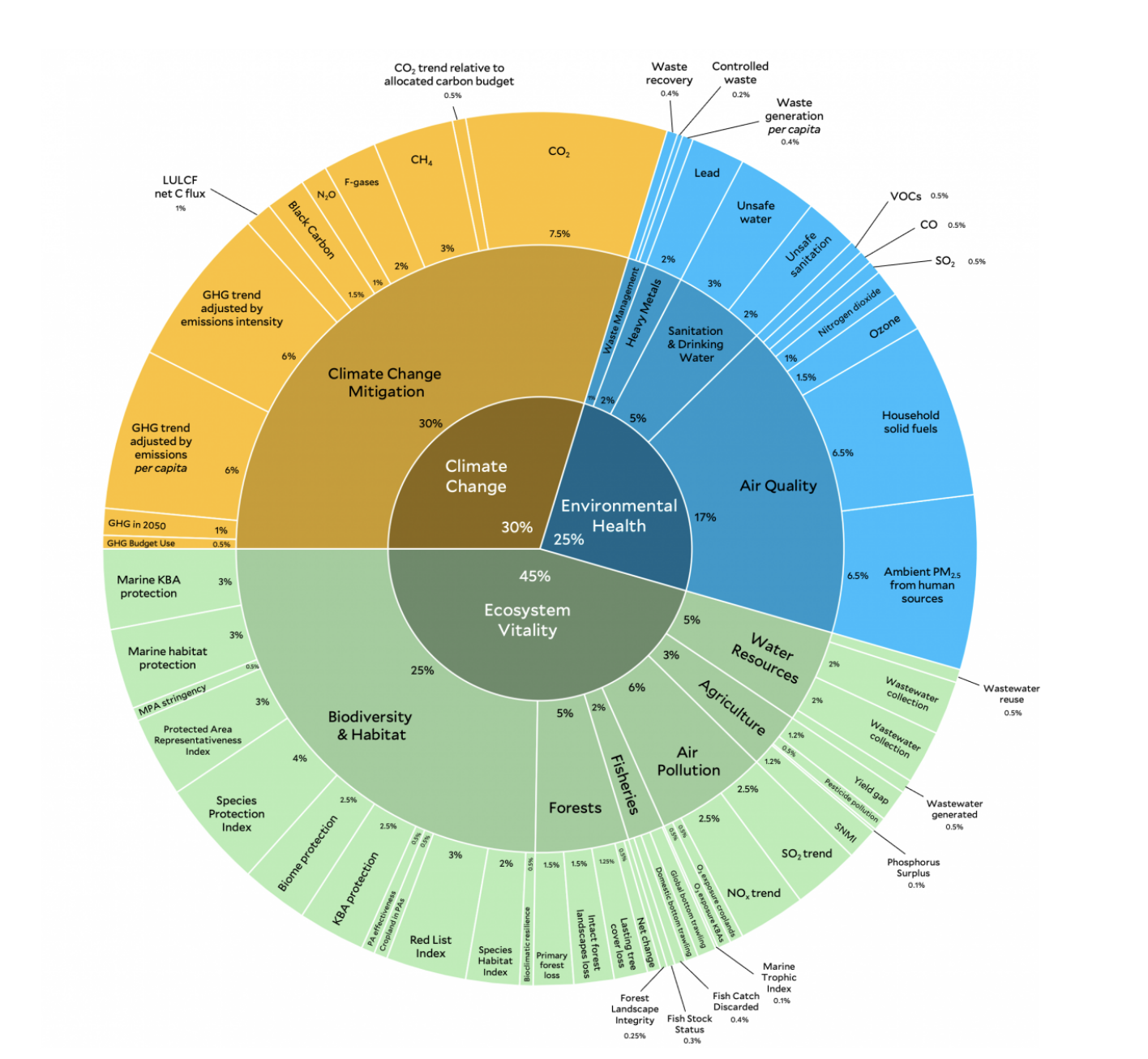

- EPI scores are positively correlated with a country’s wealth, although after a point, increasing wealth yields diminishing.

- At every level of economic development, though, some countries outperform their peers while others lag.

- And indeed, some of the poorest countries in the world outperform some of the richest.

- In this regard, factors other than wealth, such as investments in human development, rule of law, and regulatory quality, are stronger predictors of environmental performance.

- With its broad set of metrics across a wide range of environmental issues, the 2024 EPI reveals fundamental tradeoffs across different aspects of environmental performance, underscoring that no country can claim to be on a fully sustainable trajectory.

- Wealth allows countries to make investments in the infrastructure required to provide clean drinking water, safely manage waste, and rapidly expand renewable energy. But wealth also leads to higher material consumption and its associated environmental impacts, such as higher rates of waste generation, GHG emissions, and ecosystem degradation.

- Many countries with high scores in some Ecosystem Vitality metrics — such as those measuring the pollution from pesticides and fertilizers in agriculture, the integrity of forest landscapes, and the use of destructive fishing methods — do so because their economies are stagnant and underdeveloped.

- These tradeoffs underscore the urgency of international cooperation and cultural changes in the type of development societies value. Developing countries must be careful not to repeat the mistakes of nations that followed a dirty and unsustainable path to industrialization.

- On the other hand, rich countries need to decouple their consumption from environmental degradation and use their wealth to help developing countries leapfrog to a path of truly sustainable development, preserving their biodiversity and other global commons for the benefit of all humankind.

- Persistent Gaps in a Data-Rich World:

- An unprecedented availability of environmental data, including exciting recent developments in machine learning and remote sensing, underpin the innovations introduced in the 2024 EPI.

- Nonetheless, crucial data gaps persist, creating serious challenges for robust, data-driven policymaking.

- For years, the EPI team has called attention to the dearth of high-quality, standardized data on solid waste, toxic waste, and wastewater management around the world, especially in developing countries. These data gaps hamper the ability of policymakers to tackle the worsening plastic pollution crisis and to advance the world toward a circular economy.

- The world also continues to lack robust data on the protection of wetlands, grasslands, and other important ecosystems that remain difficult to characterize with remote sensing technologies.