Women, marriage and labour market participation

| “When women are empowered, they immeasurably improve the lives of everyone around them—their families, their communities, and their countries.” – Prince Harry |

Relevance: GS I and II (Social Issues and Justice)

- Prelims: Women’s labour force participation; Nobel 2023 in Economics; National Creche Scheme;

- Mains: Issues related to – Married/Working Women/Gender Pay Gap; National Creche Scheme;

Why in News?

Women’s labour market participation is often concomitant with enhanced economic prospects and better household decision-making power.

Findings from Recent observations:

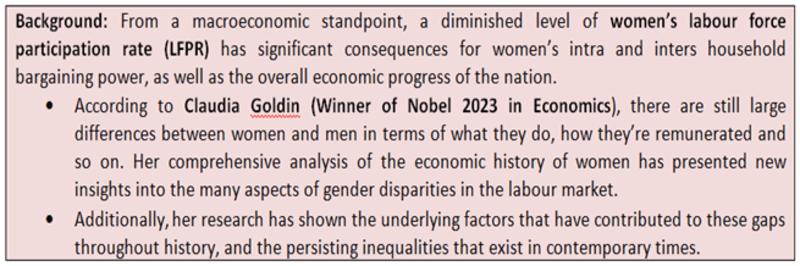

The World Bank estimates (2022) show that the worldwide LFPR for women was 47.3% in 2022. Despite the remarkable advancements observed in the global economies, there has been a persistent decline in the labour force participation rate (LFPR) of women in developing nations.

- Women workforce participation in developing countries: Globally, however, the level of female labour force participation remains relatively low.

- Indian Scenario: The estimations also indicate that female labour force participation in India between 1990 and 2022 has decreased from 28% to 24%. This fall has impeded their growth and hindered their ability to achieve their maximum capabilities.

The major cause for low woman participation in workforce:

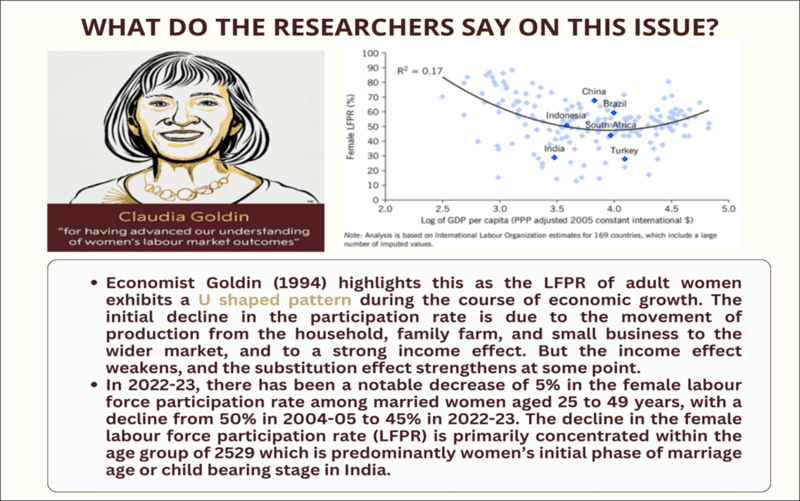

- Social Norms and Woman work participation: The labour market entry of women is influenced by a range of individual and societal factors, perhaps impacting married women to a greater extent than their unmarried counterparts.

- Marriage:

- Firstly, the institution of marriage amplifies domestic obligations for women while concurrently imposing many social and cultural impediments that affect their participation in the workforce.

- Secondly, the labour force shows that married women lack to update on literacy skills, which affects their growth progress in the labour force after getting married, as opposed to their well educated counterparts. This leads to less promotions and affects the career growth cycle of woman.

- When analyzing the female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) based on the Usual Principal Status (UPS) and Usual Principal and Subsidiary Status (UPSS) categories in India’s NSSO Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) survey (25 to 49 years), it becomes apparent that married women show a considerably lower employment proportion under the UPS status when compared to the UPSS status.

- Education: The marriage and social constraints like factors encompass women’s limited educational attainment, less mobility as a result of increasing family obligations, and societal disapproval associated with women in employment outside the domestic sphere.

Other issues:

- Freedom and Flexibility of work: When women decide to resume their professional careers upon marriage, they tend to exhibit a preference for some employment opportunities that offer enhanced flexibility and are situated in close proximity to their residences.

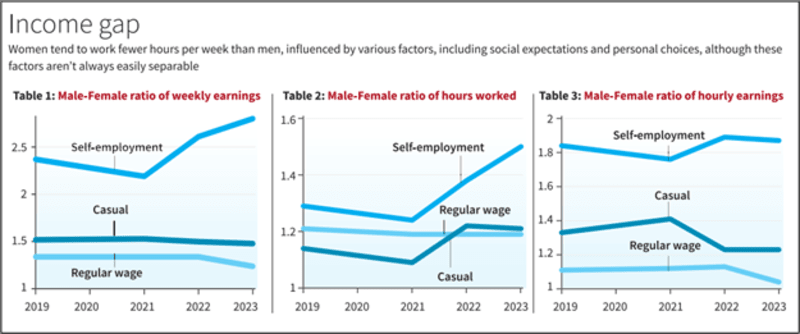

- Gender-Gap issues: Women also encounter gender asymmetrical professional costs as a result of several societal constraints, resulting in gender disparities in premarital career selections, income inequality, age at marriage, and decisions about fertility decisions.

- From wealthy background: It has been observed that women of the upper strata tend to adhere to stringent societal standards by predominantly assuming domestic roles. Conversely, women from the lower strata are more inclined to engage in the labour market, primarily driven by economic constraints that stem from poverty.

- Feminization of Agriculture: Empirical analysis that relates to the allocation of female labour across diverse industry sectors in India demonstrates that agriculture remains the prevailing sector in terms of female employment.

Way Ahead:

- Need for Day-Care services and Policies: The absence of adequate daycare services frequently acts as a disincentive for female labour force participation. Therefore, it is imperative to enhance the quality and accessibility of daycare services/creches for employed women across various socioeconomic strata, encompassing both formal and informal sectors.

- The government has enacted initiatives such as the National Creche Scheme for the Children of Working Mothers. The implementation of such schemes is imperative in both the public and private sectors.

- Need for job well-being and security provisions: The implementation of work settings that prioritize the needs and wellbeing of women, the provision of secure transportation options, and the expansion of part-time job possibilities would serve as catalysts for the greater participation of women in the labour market within India.

- Reducing the gap between social expectations and her personal growth: Solutions to pursue female LFPR have underscored the noteworthy impact of social and cultural elements on women’s choices about their entry into the labour market. Hence, considering the marital status/social constraints, their socio-economical outcome in the Indian labour market should be focused and made aware of.

Women in India are subject to a number of social and economic disadvantages that manifest from birth, continue throughout their lives, and that limit their access and opportunities. However within this challenge lies huge untapped potential, closing the employment gap between men and women could expand India’s GDP by close to a third by 2050.